see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

see section on Norway

SEEurope report

by Inger Marie Hagen and Anne Mette Ødegård (Fafo Institute for Applied Social Science, Oslo)

The present article has three parts. First we briefly review the process concerning the Statute (or the new Law on European Companies) and second we review the Directive. EU directives have been implemented in Norway in two different ways: through laws and through collective agreements. As an example, the Directive on European Works Councils is part of the National Agreement between LO and NHO and is also included in a number of other national agreements (between other trade unions and other employers’ associations) As a counter-example, the new Directive on Workers’ Information and Consultation (Dir 2002/14) forms part of the forthcoming law on the working environment (intended to pass through Parliament this spring). Concerning the Directive on workers’ participation in European Companies, implementation is taking “the legal route”. The SE directive is being implemented in Norway by way of regulation.

Implementing the SE statute in Norway

Nordea is the first company in the financial sector to make a formal decision [to become an SE])…Our trade union faces a major challenge and this is extremely exciting…. The fact that Nordea is the first company to take advantage of this possibility is positive. The union officials (at Nordic level in the financial sector) have been far-sighted enough to establish a structure for dealing with workers’ participation across Nordic borders. This structure is adjusted to Nordea’s way of organising their business as a corporation and not only activities in individual countries. The union representatives at Nordea have also – at Nordic level – established forms of collaboration and levels of decision-making which take care of the need for negotiations and information exchange between employees and management (Financial Sector Union of Norway).

To summarise – as one trade union official did when we interviewed him: “if it [workers’ participation and codetermination] is good, the European Company makes it better, if it is bad – it gets worse”.

There has been little public debate in Norway concerning the SE or how to implement the Statute and the Directive. For example, we searched the two main financial newspapers in Norway and could find only two articles dealing with the subject in all of 2004 and 2005. Within the trade unions there have not been any major (or visible) debates, nor has the fairly strong Norwegian “NO-movement” targeted the Statute (or the Directive) in their ongoing campaign. Hearings (consultation rounds) were arranged concerning both the Statute and the Directive. Concerning the Statute, of 51 recipients (both state bodies and employer and employee organisations, as well as a number of law firms) only 13 submitted comments. Concerning the Directive, after sending the proposed “Norwegian version” to 63 recipients, the Ministry responsible for the hearing (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs) did not alter its proposal on any point.

Norway has a reputation for being “better than the EU countries themselves” when it comes to implementing statutes and directives. However, in this case we have been rather slow. The debate in Parliament was delayed several times. According to our informants, however, there is nothing political behind this.

The present article has three parts. First we briefly review the process concerning the Statute (or the new Law on European Companies) and second we review the Directive. EU directives have been implemented in Norway in two different ways: through laws and through collective agreements. As an example, the Directive on European Works Councils is part of the National Agreement between LO and NHO and is also included in a number of other national agreements (between other trade unions and other employers’ associations) As a counter-example, the new Directive on Workers’ Information and Consultation (Dir 2002/14) forms part of the forthcoming law on the working environment (intended to pass through Parliament this spring). Concerning the Directive on workers’ participation in European Companies, implementation is taking “the legal route”. The SE directive is being implemented in Norway by way of regulation.

In the third section we make some brief comments on the potential impact of European Companies on the Norwegian system of workers’ participation and codetermination. Throughout, we focus on implications for the Norwegian system of employee directors at board level. As in Denmark and Sweden, Norwegian employees may take one third of the seats, even at corporate level. Whether it will be possible to achieve similar representation rights if a Norwegian company or corporation should choose to become an SE is the key issue.

1. Statute

On 4 March 2005 the Norwegian Parliament, the Storting, adopted a new law (Lov om europeiske selskaper ved gjennomføring av EØS-avtalen vedlegg XXII nr. 10a (rådsforordning (EF) nr. 2157/2001) (SE-loven) to implement the SE Statute. Two parliamentary parties, the Senterparti (originally the Farmers’ Party) and the Sosialistisk Venstreparti (the Socialist Left) voted against the new law because, in their opinion, it will make it easier for companies to move their head office abroad. However, their resistance may also be connected to the fact that they are the major “NO” political parties.

The EEA Agreement obliges Norway to implement this Statute (Art. 77). The Parliament’s EEA Committee, on 25 June 2002, agreed that the SE Statute should be part of the EEA agreement, and thereby a part of Norwegian legislation.

In Norway an SE will be set up according to the regulations governing public limited liability companies, as long as these do not contradict the regulations in the SE Statute. This is also the case if an SE is established after a merger with another company.

If an SE decides to leave the country, it will be obliged to insert “company on the move” in all documents and letters after the decision has been taken. The Council of State together with the King can prohibit a move abroad by an SE if it is against the public interest. For companies in banking, insurance, finance and share trading it is also necessary to obtain permission from the Company Registry (Foretaksregisteret).

The typical Norwegian corporate governance structure consists of the general assembly, the company board and the management. The employees are entitled to one seat on the company board in companies with more than 30 employees and one third of the seats in companies with more than 50 employees. The Norwegian system does not have anything parallel to the regulations in the SE Statute. The new law on SEs makes it possible to choose between a one-tier or a two-tier structure. For both alternatives, the regulations in the law on public limited liability companies concerning company boards and directors will be obligatory as long as they do not contradict the regulations in the SE Statute. The management organ shall have a minimum of three members.

In the two-tier system, the supervisory organ shall consist of a minimum of five members. Members shall be elected by the general assembly. In the one-tier system, the Norwegian regulations on company boards will apply to the management organ as long as they do not contradict the regulations in the SE Statute. The board shall summon an extraordinary general assembly when the auditor or shareholders representing a minimum of 5 per cent of the shares demand it.

2. Directive

As already mentioned, the SE directive is being implemented in Norway by way of regulation (precept) to the Act. The regulation is fairly complicated and perhaps the only (or at least the most important) result of the Parliamentary debate, was the decision to ask the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs responsible for the regulation to produce an instruction on how to use and interpret it. The Ministry itself argues that the main argument for making this into a formal regulation and not a legal Act is that the rules concerning workers’ participation are very detailed and that the Directive “in all probability” will be altered in the near future.

The level of complexity of the regulation makes it difficult to give a clear overall presentation of the Norwegian regulation. However, we will concentrate our contribution on the following areas: i) dispute resolution mechanisms, ii) rules concerning SEs with subsidiaries or branches in Norway, but domiciled in other countries and iii) rules concerning SEs established in Norway

i) Dispute resolution mechanisms

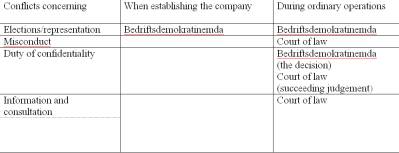

The Ministry did not reach a decision on whether the regulation is to be regarded as a collective agreement or not. In Norway, the Industrial Disputes Court (Arbeidsretten) settles disputes concerning collective agreements. As a consequence of the lack of a decision, the Arbeidsret does not have a role if the company does not follow the regulation. The following system has been established:

The Bedriftsdemokratinemd (“committee on local/shop floor industrial democracy”) is a joint social partner committee subject to the Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs. This committee has the authority to grant exceptions from the different legal Acts concerning employee directors and the corporate assembly (bedriftsforsamling). In addition, it has the authority to sanction corporate systems or agreements on workers’ participation and the establishment of employee board representation at corporate level. Employees in Norway may demand representation on corporate boards by the same Act which governs company level (and the same requirements concerning size of company and number of directors), but the committee typically has to define the corporation as such (number of companies included and so on). The committee is also the dispute resolution mechanism for conflicts regarding European Works Councils. SNB, RB, SEs, subsidiaries, branches, local trade unions and employees may apply to the “nemd”.

Possible breaches of the regulation are regulated in §14. If less than one year after having registered as an SE, major changes take place in the company (or any subsidiary or branch) and these changes would have given the employees a higher degree of participation than the present rules if they had been implemented prior to registration, then the rules on employee participation in the initial agreement may be considered a misuse of SE procedures. However, if the company is able to prove that the changes were due to other reasons, it is not considered as misuse.

In the event of misuse of procedures, RB or representatives of more than half the employees may demand renegotiation. In other words, the burden of proof is on the company.

ii) SEs with Norwegian

The main point here is the allocation of the Norwegian seats in the special negotiating body. This is based on number of employees. If they represent at least two thirds of the employees, local trade unions (alone or a combination of different unions) may appoint the representatives. In the absence of local trade unions representing two thirds of the employees, or where there is no trade union representation or conflict among the trade unions, there is an election involving all employees, following the same procedure as the election of board members. The main point is the principle of “by and from among”: to be eligible one must be employed by the company – trade unionists not employed by the company (for example, central officials) may not be elected.

iii) Norwegian SEs

The same rules are used for allocating the Norwegian seats in the SNB. The mandate of the SNB and the procedures for reaching agreement (for example, simple majority unless it has been decided otherwise) are very important because of Norwegian legislation on employee directors. In order to reduce representation at board level (one- or two-tier systems) the SNB requires two thirds of the votes (and these votes must represent at least two thirds of the total number of employees). However, this two-thirds requirement is not needed when i) the SE is established by merger and the right of representation covers less than one quarter of the employees in the companies involved in the merger, or ii) when the SE is established by forming a holding company or subsidiary and the right of representation covers less than half the employees, or iii) when an SE is established by conversion. In this case, the SNB agreement must lay down a level of participation (defined as information, consultation and representation at board level) which is at least the same as prior to conversion.

The SNB may – subject to the same requirements as in the previous section – decide not to enter into negotiations or to terminate negotiations. However, this does not necessarily mean than the company comes under the standard regulations. The SNB may decide to use the regulations on information and consultation from other countries with SE employees. These rules do not apply to conversions.

The standard regulations (§11 in the Norwegian regulation) are applied i) if the parties agree to do so and ii) if an agreement is not reached within the deadline (six months after establishing the SNB or – if so agreed – one year).

Again, the rules on board-level representation are important due to the Norwegian situation. The standard rules of representation shall apply if the parties agree to use them. Moreover, these rules may be applied in conversions only if such rules already existed, and in the case of a merger if such rules existed in at least one of the companies and at least one quarter of the employees were covered by this rule. The SNB may make exceptions.

The participating companies must cover the SNB's costs, including at least one expert. During the negotiations the representatives of relevant trade unions may be present when requested.

The agreement between the SNB and the participating companies shall include (in addition to the provisions mentioned above):

a) the scope of the agreement;

b) the composition, number and distribution of RB seats;

c) RB functions and procedures;

d) the number of RB meetings;

e) the economic and material resources of the RB;

f) the relevant procedures if the SNB agrees to establish one or more procedures for information and consultation replacing a representative body;

g) if an agreement on representation is reached, the details of this representation, including board-level representation (employee director, the right to recommend or to veto) and the election procedures connected to these different rights;

h) date of commencement and duration, cases where the agreement should be re- negotiated and renegotiation procedures.

The SE – in Norway?

The Norwegian system of employee participation is, by international comparison, among the very best. The right to board representation in the Nordic countries is unique. What then are the possible consequences for our system of codetermination and participation if a Norwegian company should become an SE? Will it be possible to maintain board representation at present levels? In the largest Norwegian companies the number of Norwegian employees is steadily decreasing, while the number of employees abroad is increasing – in many cases they already outnumber their Norwegian colleagues.

The Norwegians elected to the SNB – bringing their extended rights into the negotiations – may very soon be a minority, as will the proportion of employees in the companies covered by these rights. Using the present Norwegian level of codetermination and participation as a starting point, it is hard to foresee any improvement as a result of SE formation. Again, Norwegian board representation is our major concern.

However, when evaluating the impact of the right to board representation – as we have done in a number of Fafo projects – both the employee representatives and CEOs emphasise a very significant prerequisite for attaining influence as a board member: you must combine being a director and being elected as a corporate trade union officer (CTU).

The CTU system may require some explanation. If a corporation has more than 100 employees, the National Agreement requires that a corporate (concern) committee be established. This committee may be compared to an EWC, but at national level. If the number of employees exceeds 200, the National Agreement states that a CTU may be needed. However, the Agreement ascribes no rights to the CTU in relation to management. The management must acknowledge or approve the CTU through a local agreement.

However, we find CTUs in almost all the largest Norwegian corporations. Their level of influence may vary, but many of the CTUs – as well as the CEOs – who talked to us emphasised the important role of CTUs, especially when it comes to restructuring or organisational development. Close collaboration between the parties was one of the most important elements in processes of change.

We bring this up here because our findings indicate that the importance of board representation is closely connected to the CTU system: that is, board representation is an important source of influence only if the employee director is also a CTU or at least is a leading trade unionist at corporate level. This is even acknowledged by the CEO: “if the director is not a CTU or if the CTU does not hold the position of director, he does not represent a significant collaborator or partner to me”.

These findings have two implications or interpretations. The pessimistic one is that if the SE implies deteriorating rights at board level it may impact the whole system of collaboration at corporate level. Much more positively, the experiences connected to the CTU system may imply that Norwegian companies, even if they transform into European Companies, will establish systems of participation similar to present practice. It is important to keep in mind that the CTU system is a voluntary arrangement: it is not found in the collective agreement at central level. This also implies that CTUs have to prove – both to the management and to the employees – that this system is important both for the running of the company and as a tool of employee influence.

Some Norwegian companies have started to export “the Norwegian model” – the CTU at Norske Skog (one of the world’s leading paper manufacturers) has recently become a sort of “world or global” CTU. Another example is Kværner, which has included employee representatives at board level at their US shipyard (in Philadelphia). Both these corporations have long and strong traditions of collaboration and also strong trade unions.

These Fafo findings underline the views of the trade unionist quoted at the beginning of this contribution: if a strong employee influence already exists, transformation into an SE is not a threat to our present system of participation. However, as we have tried to identify by using the CTU as an example, the trade unions must demonstrate their ability to contribute to company growth and profitability. If not, the management may choose not to acknowledge the CTU, so limiting the importance of board representation.